You probably hear it referenced with every college football game you tune into. Commentators and spectators alike banter about it consistently. For Iowa State, we often here it bandied about in regards to Wally Burnham’s schemes.

Yet, are “bend but don’t break” defenses a real thing? A strategy employed by defensive minds to keep offenses from putting points on the board? And most importantly, does it work?

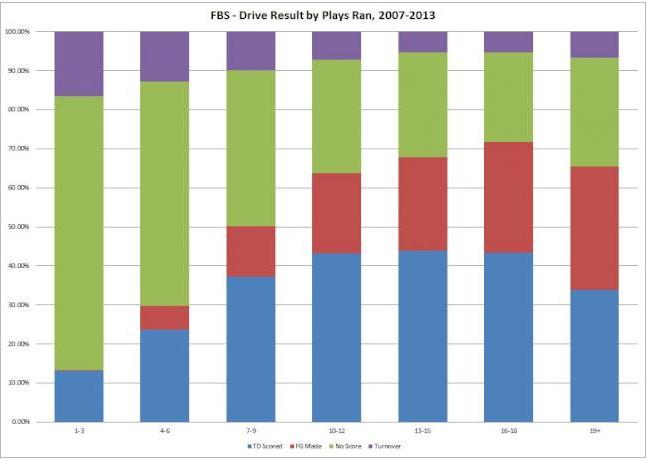

To investigate, I analyzed every drive by every FBS team from 2007-2013. I separated by the length of the drive in terms of number of plays and combined them into groupings of three plays (1-3, 4-6, etc…). I then compared how those drives ended, either with a touchdown, a made field goal, a turnover, or the rest of the possibilities that include not scoring. Each column on the chart captures 100 percent of the ways a drive ended that contained the given number of plays.

Here is the chart:

As you can see, the longer offenses are on the field they actually have a tendency to score more often and commit turnovers at a slower rate.

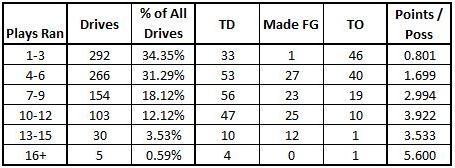

Above is the corresponding table for all of these FBS games. It breaks out the data to the values but the key column is on the far right with points per possession. Once a drive gets to seven plays, the points per possession jumps to nearly three at 2.992. For reference, just nine defenses in 2013 allowed an average of three points per possession or more and just 12 offenses scored at that clip or better. Scoring an average of 2.992 points per possession once a drive hits seven plays is quite significant.

The “bend but don’t break” philosophy is much more of a fallacy. But, I think it has some validity to it. It just gets misconstrued.

I have always defined the “bend but don’t break” defense as a scheme where the goal first and foremost is to eliminate the big play. One offshoot of that is the premise that the offense will eventually make a mistake as the plays in the drive continue to mount. Whether it be a turnover, eventually forcing a third and long, or a miscue as the field shrinks – a shrinking favors the defense because they have less ground to defend.

The first part of that definition I still believe to be true, prevent the big plays. But it isn’t for the end game of forcing, or perhaps even hoping, for a mistake. Because as the 145,000+ drives from 2007-2013 above show, offenses are ultimately more successful the longer they are on the field.

But how does Iowa State tie into all of this? Wally Burnham’s defenses are also thrown under the “bend but don’t break” umbrella. Though, I can’t say that I have ever heard Wally say anything along those lines or even infer that it is his philosophy. Maybe it is somehow a part of his scheme but my guess the only real piece that translates over is the prevention of big plays.

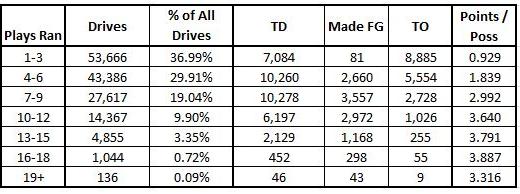

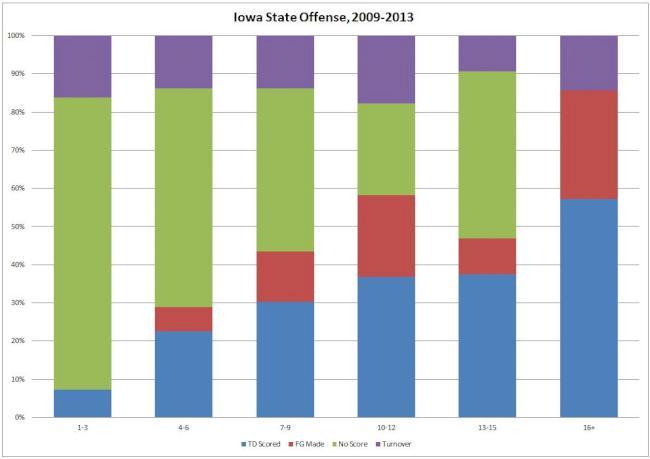

Either way, below is the bar chart from the Rhoads era defenses and how opponents did as drives prolonged in number of plays:

The result is very similar to the FBS average. The two small caveats show up in turnovers forced as drives get into the seven to nine play range and the frequency of which they give up touchdowns on drives of 16 plays or more being at 80% (note the very small sample size below, though).

Again, here is the corresponding table with the data that is in the chart above. Again, look at how the points per possession jumps at seven plays.

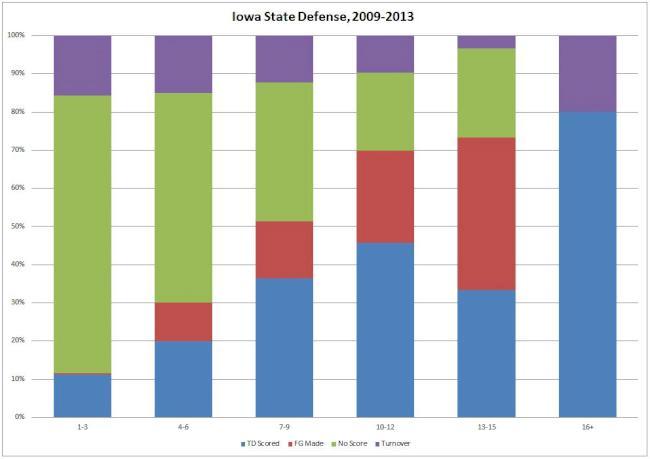

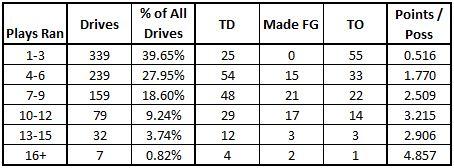

And, just for kicks, the Cyclone offense as well:

A couple of points here that is completely outside of the scope of the rest of this column: 1) there is a quite a difference in the touchdown percentage for ISU’s offense on drives of one to three plays when compared to the rest of the country and, 2) while there is a jump in scoring as drives prolong it is much less pronounced than the rest of the country and that is likely due to turnovers (look at the column for 10-12 plays and 16+).

Again, the corresponding table is also included.

Hopefully what you have learned today is the “bend but don’t break” defense is a complete myth. The main premise of it is likely true, but who wouldn’t want to prevent big plays? The question may be to what extent are you willing to prevent them? Does it behoove the defense to avoid the big play in trade for a three or four yard gain from the offense? This data seems to point to that being a bad deal for the defense. Because the longer the offense keeps moving the more likely they are to score.

When reduced to a simple statement of, “the longer the offense is on the field the more likely they score” seems obvious. But, the data proves that out tremendously and it flies in the face of the conventional wisdom.

More often than not bending defenses does break them.