Part 2:

"In all these years that young Black men have played, starred in and contributed so enormously to the game of college football that they now dominate, I don’t recall any who have been so honored. Especially one who wasn’t an all-American, all-conference or all-anything. Trice played only one game, at home against Simpson College, before dying after his second.

Trice’s tale, which I researched many years ago for my thesis, is one of the most remarkable in a sport full of them. He was more than a pioneer as the first Black football player at Iowa State and one of the early Black football players at a predominantly White college. Trice became an inspiration. Why? Because of what he aspired to do for others.

Trice left his Cleveland home for Ames in 1922, with the goal of learning to farm as had his father, who died when Trice was 7. And he wanted to farm in the South, where his parents were born, and for Black Americans who predominated that region. What better place to learn the trade than Iowa State, which produced the most famous Black scientist in America, botanist George Washington Carver? Carver also had been a part of the Iowa State football program,

serving as its trainer for a spell.

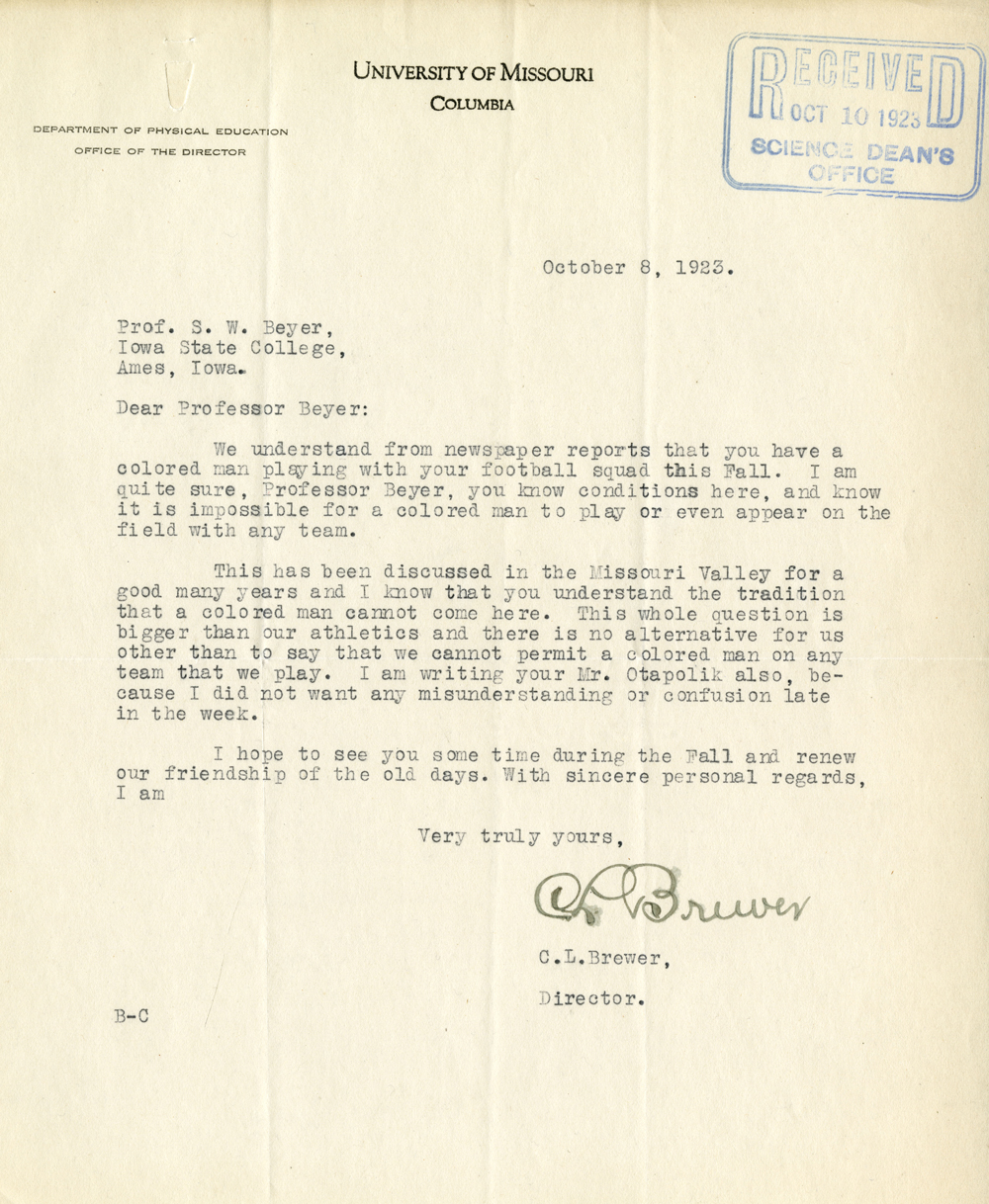

But like the other few Black students in Ames, Trice was left to fend for himself, at the same time a local KKK chapter was sprouting. He had to secure housing off the de facto Whites-only campus. That meant renting a room in a house that catered to Black students and provided board. And finding work to pay for it, which Trice did, as a janitor. It aided him a year later in bringing his teenage bride, Cora Mae, to live with him. He said goodbye to her before joining the team for an overnight train trip Oct. 5, 1923, to a game against Minnesota the next day.

College football was a much more perilous game then. Nearly two decades earlier, then-president Theodore Roosevelt

summoned the bosses of the major football schools to clean up a game that in 1905 saw several players killed. It resulted in outlawing, for example, the flying wedge, when blockers locked arms and steamrolled would-be tacklers.

The few Black players for White colleges often found themselves objects of the game’s violence. When Paul Robeson in 1915 integrated the team at Rutgers, where he became a two-time all-American,

he was targeted — by his own teammates.

Trice couldn’t blend in at Minnesota’s Northrop Field. He wasn’t a light-skinned Black man with wavy hair. Trice was dark skinned, a deep chocolate. He wore his tuft of tightly coiled black hair high on his crown and closely cropped on the sides. His opponents took note.

Trice was an object of their attack early, injuring his shoulder in the first quarter. In the third quarter, Trice, playing defensive end, was faced with an avalanche of linemen clearing a path for a Gophers ballcarrier, a formation similar to the one that had been outlawed. Trice lowered his body and began a roll to break up the oncoming blockade.

He was trampled. Maybe on purpose.

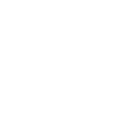

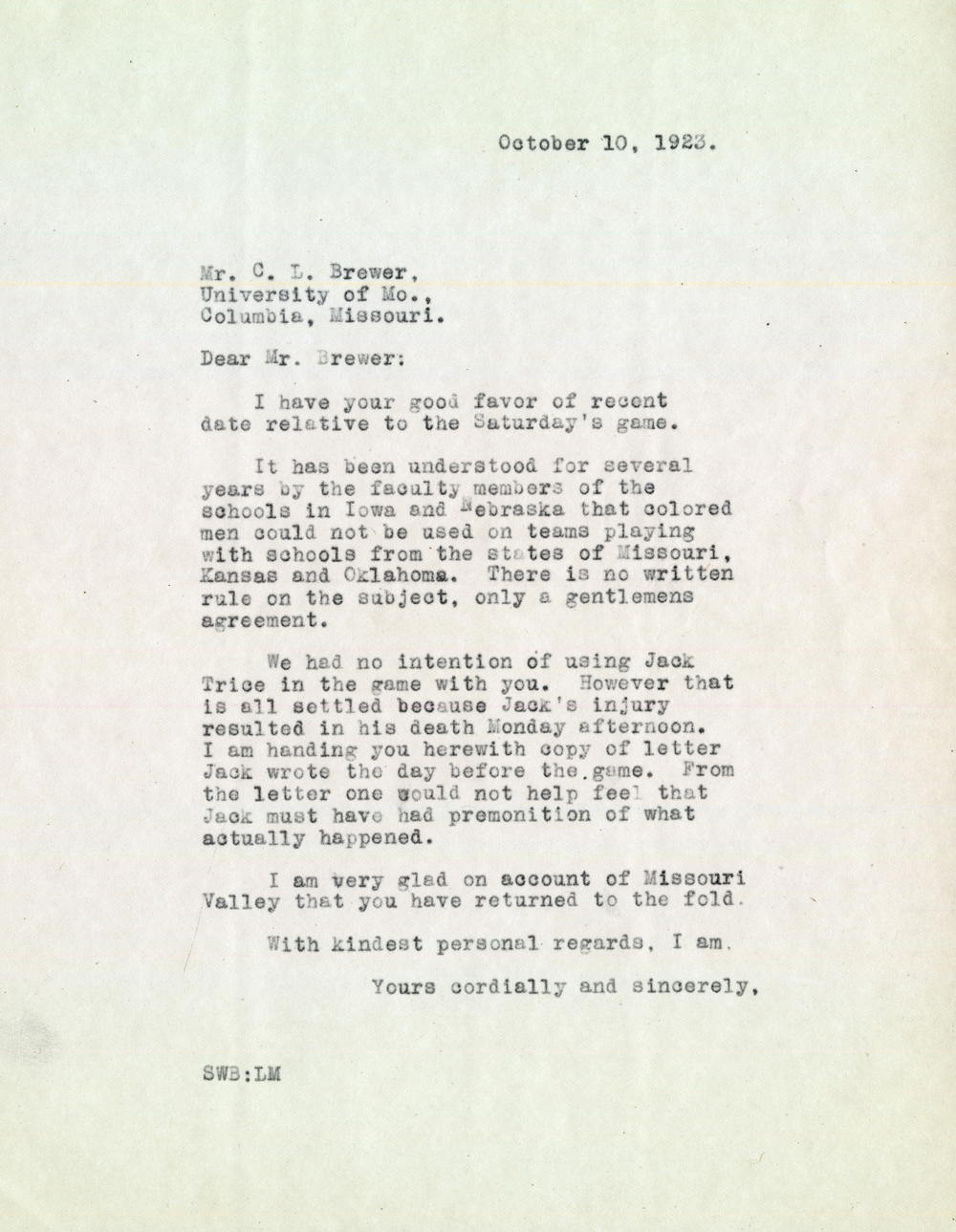

Trice couldn’t make it on his own to the sideline. But after teammates helped him, the team doctor ordered him to a hospital. He was released, prematurely some have suspected, to make the team’s overnight train ride back to Ames atop what was said to be a straw mattress in a drafty boxcar.

Trice was rushed to Iowa State’s infirmary. By Monday, his condition worsened. It was believed he had suffered a broken collarbone and internal injuries that some said should have been treated in Minnesota. The Iowa State Daily later that day announced his death. “With him since his injury has been his wife, who nurses in the hospital say is bearing up bravely,” the newspaper reported.

Classes were canceled the next day for a campus funeral. Cora Mae gave university president R.A. Pearson a letter she found in her late husband’s belongings and granted him permission to read it to the throng. It read in part:

To Whom it may concern:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, & self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body & soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part.

Jack

A memorial plaque was placed in the corner of the gym. It was forgotten about until a tutor noticed it half a century later. The Iowa State Daily wrote a story about the discovery. A class dug deeper. A student movement began to honor him more prominently.

It all spurred the Jack Trice Memorial Stadium Committee, which culminated in 1997 when this ordinary and once-forgotten athlete was memorialized, with his name unveiled on the home stadium where his game is scheduled to be played Saturday. It is, by the way, the only stadium in major college football whose name commemorates a representative of Trice’s race, someone colleges once didn’t want to let play.

In all these years that young Black men have played, starred in and contributed so enormously to the game of college football that they now dominate, I don’t recall any who have been so honored. Especially one who wasn’t an all-American, all-conference or all-anything. Trice played only one game, at home against Simpson College, before dying after his second.

Trice’s tale, which I researched many years ago for my thesis, is one of the most remarkable in a sport full of them. He was more than a pioneer as the first Black football player at Iowa State and one of the early Black football players at a predominantly White college. Trice became an inspiration. Why? Because of what he aspired to do for others.

Trice left his Cleveland home for Ames in 1922, with the goal of learning to farm as had his father, who died when Trice was 7. And he wanted to farm in the South, where his parents were born, and for Black Americans who predominated that region. What better place to learn the trade than Iowa State, which produced the most famous Black scientist in America, botanist George Washington Carver? Carver also had been a part of the Iowa State football program,

serving as its trainer for a spell."